Josué García-Arch (1), Solenn Friedrich (1), Xiongbo Wu (2), David Cucurell (1) y Lluís Fuentemilla (1)

(1) Dept. de Psicología de la Cognición, Desarrollo y Educación, Universidad de Barcelona, España

(2) Dept. of Psychology, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, Alemania

(cc) Josué García-Arch.

According to current research, what we think of ourselves (our self-concept) is shaped by, mainly, the positive feedback that we receive during our daily lifes. However, contrary to this view, in a recent study we showed that we tend to incorporate external information into our self-beliefs when that information matches how we already see ourselves. These findings suggest that we prioritize internal coherence rather than the mere pursuit of a positive self-view.

Imagine someone tells you, “You’re such a good listener,” or instead, “You can be a bit impatient.” Both remarks carry evaluative information (positive in the former case, negative in the latter), yet in most cases we tend to embrace the compliment more readily than the criticism. Research in cognitive science shows that when self-relevant feedback has positive or negative valence, people tend to process and integrate favorable information more readily. This tendency is thought to contribute to optimism biases and positively skewed self-views (Korn et al., 2012; Sharot & Garrett, 2016). However, there are other critical aspects to take into account. Beyond the pursuit of considering ourselves in positive terms, we also have a fundamental need to maintain a stable and coherent self-image (Campbell et al., 2003), and that need would be seriously undermined if self-views were continuously reshaped solely on the basis of whether the information we receive is “positive” or “negative”. Think about it for a second, would you even feel the same person if you internalized every compliment that came your way? After all, if someone told me I was “super extroverted” and I truly took it to heart (I’m definitely not), I might feel motivated to go to that “cool party” I’ve been avoiding, and end up wondering what on earth I’m doing there (most likely suffering in silence).

To make things a bit more complicated, because the self-concept is typically skewed toward the positive in healthy adults, valence and congruence are often confounded. For example, receiving positive feedback about a trait we already endorse, say, being told “Everyone thinks you’re very funny” when we already see ourselves that way, is both “good news” and “self-view stabilizing.” In such moments, positivity and congruence converge into the same signal, making it difficult to determine whether a cognitive or neural response reflects the rewarding nature of the feedback or its reinforcing effect on self-stability. Unless these dimensions are carefully disentangled, we risk attributing to positivity what may actually be the effect of congruence.

In a recent study (García‐Arch et al., 2024), we set out to resolve this ambiguity. To do so, we designed a social feedback paradigm in which participants first evaluated themselves on a wide range of personality traits and later received feedback (purportedly from peers) about those same traits while we recorded their brain activity with electroencephalography (EEG). Crucially, the feedback was experimentally manipulated so that it could be positive or negative (valence), and either align with or contradict participants’ prior self-views (self-congruence). This allowed us to disentangle whether we are guided primarily by the rewarding nature of positive information or by the stabilizing force of self-congruence.

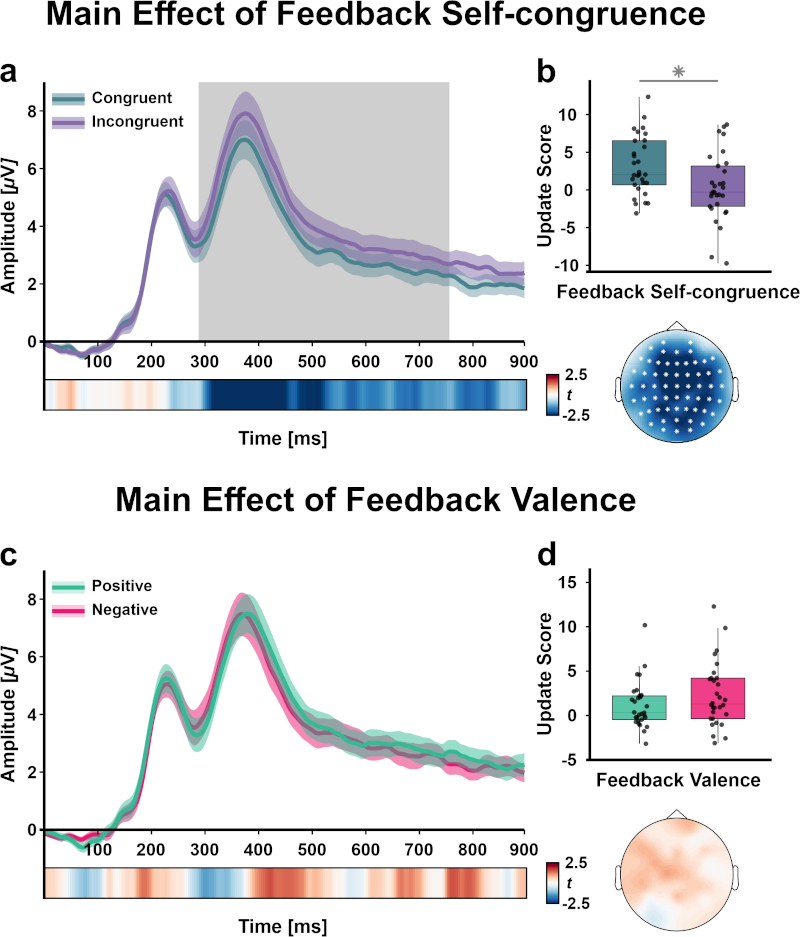

The results (see Figure 1) supported the idea that congruence, rather than valence, drives feedback processing and self-concept updating. At the behavioral level, we measured how much participants changed their confidence in their self-descriptions after receiving feedback. The pattern was clear: they consistently incorporated feedback that fitted with what they already believed about themselves, whether positive or negative, while dismissing feedback that conflicted with their prior self-views.

Importantly, the neural data told a similar story. We examined the brain’s electrophysiological responses as feedback appeared on the screen. Here, congruence effects emerged quickly, between roughly 300 and 750 milliseconds after feedback onset, and were distributed across widespread regions of the scalp. This suggests that the brain rapidly detects whether incoming social information fits or clashes with the self-schema. By contrast, feedback valence (positive vs. negative) did not elicit significant differences. Together, these findings indicate that when people process feedback about themselves, the first and most powerful filter is whether such input is reinforcing or challenging its current content.

Figure 1. Feedback congruence, not valence, drives how people update their self‐beliefs. a) Brain responses (EEG) to self-relevant feedback that either matched participants’ prior self-views (congruent) or contradicted them (incongruent). The curves show mean EEG voltage, a measure of the brain’s electrical activity averaged across trials and electrodes. Larger voltage differences reflect stronger neural reactions to the feedback. Incongruent feedback triggered a greater, sustained response between ~300 and 750 ms, indicating that the brain rapidly detects when new information does not fit the existing self-concept. b) Update scores represent how much participants changed their self-ratings after receiving each type of feedback. Higher values mean greater belief revision. Participants updated their self-views more when the feedback was congruent than when it was incongruent. c) Neural responses to positive versus negative feedback (valence). Unlike congruence, valence did not produce observable differences in mean EEG voltage. d) Update scores did not differ significantly for positive and negative feedback, reinforcing that the key factor driving belief revision is not whether feedback is “good” or “bad” but whether it aligns with one’s existing self-views. (cc) García-Arch et al. (2024).

These findings have important implications. Prior work has attributed learning asymmetries and neural signatures to positivity alone, but this may in part be because positivity and congruence are entangled in populations with largely positive self-views. Reframing the bias as one of self-congruence clarifies how stability and coherence are safeguarded in the architecture of the self-concept. Importantly, we do not deny the existence of valence-based biases. Indeed, the very reason valence and congruence must be disentangled is that most individuals already hold positively skewed self-views. Whether this reflects the accumulation of more positive than negative feedback during early periods in life, when stability forces are still developing, or whether it reflects a positivity bias that gradually recedes as the self-concept matures, remains an open question. What our findings highlight is that the apparent preference for positive information may often be a by-product of this developmental interplay between congruence and valence. It also suggests new ways of thinking about variability across individuals and contexts. People with fragile or negative self-concepts, for instance, may show a different mapping between valence and congruence, with negative information more often serving to stabilize identity.

The broader point is that changing what we think of ourselves cannot be reduced to a simple preference for good news. The self is not only an evaluative system but also a schema of continuity, richly supported by autobiographical evidence. Congruence protects this structure from disruption, while still allowing positivity to flourish when it aligns with existing views. In practice, this means that praise or criticism only changes us to the extent that it fits the puzzle we have already assembled. Feedback processing in the self-domain, then, is guided less by valence than by the deeper imperative of preserving a coherent and stable sense of who we are.

References

Campbell, J. D., Assanand, S., & Di Paula, A. (2003). The structure of the self-concept and its relation to psychological adjustment. Journal of Personality, 71, 115–140.

García‐Arch, J., Friedrich, S., Wu, X., Cucurell, D., & Fuentemilla, L. (2024). Beyond the positivity bias: the processing and integration of self‐relevant feedback is driven by its alignment with pre‐existing self‐views. Cognitive Science, 48, e70017,

Korn, C. W., et al. (2012). Positively biased processing of self-relevant social feedback. Journal of Neuroscience, 32, 16832–16844.

Sharot, T., & Garrett, N. (2016). Forming beliefs: Why valence matters. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 20, 25–33.

Manuscript received on October 1st, 2025.

Accepted on November 25th, 2025.

This is the English version of

García-Arch, J., Friedrich, S., Wu, X., Cucurell, D., y Fuentemilla, L. (2025). Congruencia antes que elogios: ¿Cómo procesamos e integramos la información sobre nosotros mismos? Ciencia Cognitiva, 19:3, 116-119.